Animals in their natural environments effortlessly switch up their movements to hunt, escape from predators, and travel with their packs every day. By chasing cockroaches through an obstacle course and studying their movements, the Johns Hopkins engineers discovered that animals’ movement transitions corresponded to overcoming potential energy barriers and that they can jitter around to traverse obstacles in complex terrain.

A report of the findings were published Monday in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“Our findings will help make robots more robust and widen their range of movement in the real world,” says physicist Chen Li, an assistant professor of mechanical engineering and the paper’s senior author.

With mobile robots on the verge of integrating into society, it’s important that they can move through the world around them with ease and efficiency, says Li. While some mobile robots like self-driving cars and robot vacuums are already excellent at navigating flat surfaces and transitioning between movements, many critical uses—such as searching and rescuing in rubble, inspecting and monitoring buildings, and space exploration—require robots to physically interact with their terrain to traverse, rather than simply avoid, obstructions.

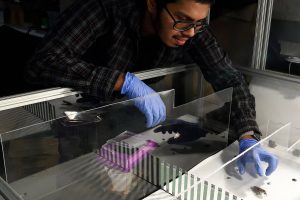

“Search and rescue robots can’t operate solely by avoiding obstacles, like a vacuum robot would try to avoid a couch,” says Ratan Othayoth, a graduate student in Li’s lab and the study’s first author. “These robots have to go through rubble, and to do so, they have to use different types of movement in three dimensions.”