From the time he was a child building with blocks in Rancho Cucamonga, CA, Michael West Jr. knew that he wanted to be an engineer. He initially set his sights on civil engineering, but after being recruited to Yale University’s football team as a linebacker, West arrived in New Haven to find he immediately needed a change of plan.

“I committed to Yale, and then I get to campus and they didn’t have civil engineering,” he said. “I was like, really? The next closest thing was mechanical engineering, which turned out to be a good choice.”

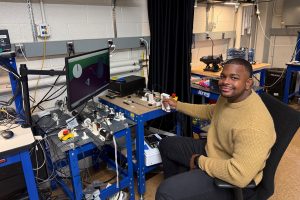

West, who earned a PhD from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, joins the Whiting School’s Department of Mechanical Engineering as a Provost’s Postdoctoral Fellow, working in Jeremy Brown’s Haptics and Medical Robotics (HAMR) lab. Following his postdoctoral term, West will join the faculty of the Georgia Institute of Technology as an assistant professor of mechanical engineering. Learn more about him and his research below:

Why did you choose engineering as a discipline and career?

My dad was a software engineer, but he did his schooling in mechanical engineering. So that was an influence. Growing up I was always interested in math. Math was always about numbers, and I was always looking for ways to apply the numbers. I took a physics course in high school, which is about as applied as math got. But we did the classic project where you make a bridge out of toothpicks, and that I really liked. This piqued my curiosity in engineering.

How did you end up at Johns Hopkins?

My wife moved here first for her OB residency at Hopkins. I had a year left in my PhD, after which I needed to find a job nearby in Baltimore. So, while finishing my PhD, I reached out to Jeremy about a postdoc position because of the work his lab does, and he said, hey, I’d love to work with you. He encouraged me to apply to the Provost’s Postdoctoral Fellowship to secure funding and luckily it worked out!

What is the main focus of your research?

You could say I’m a controls engineer for humans—I am interested in trying to study humans and human movement. With this knowledge we can build better controllers for both robotic manipulators and rehabilitation devices, including prosthetics and exoskeletons.

The themes I’m currently interested in are related to surgery and rehabilitation. And I think when I was originally hired, (Jeremy) wanted to kind of build out the rehabilitation aspect of his lab because it wasn’t something that they had done a whole lot in just yet. We’re looking a lot at sensory-motor rehabilitation for patients after they’ve had a stroke. Which is great because I wanted to get exposure to working with impaired patient populations.

What is your approach in the lab and to research in general?

In my approach I use what I like to call simple models. But I guess more apt would be interpretable models. What I’m interested in is trying to understand from a simplified approach what control techniques humans are using to produce their movement.

I think of the body as a product—as a device we all use. Stealing from a product design approach: there are classes of users. We have novice users who could be children or recently impaired people. They’re still learning, or re-learning, how to use their bodies. Then we have everyday, non-impaired users: you can think of this as an intermediate level. Then we have expert users, like athletes, surgeons, or musicians.

I want to study all these classes of users to see how they use their “device.” For a research paradigm, people like me who study motor control are interested in how humans move from one category up to the next one. Many people study going from novice to intermediate in patient populations. However, not many people study how experts acquire their skills. I’m interested in breaking into that space, and one good way is through looking into surgical training.

Why do surgeons make good case studies?

Surgeons become highly skilled dexterous manipulators in a short time frame. To me this makes the perfect research subject. Interesting questions are: How do surgeons acquire their skills? Can we quantify that? And if we can quantify that, can we make the learning process a little faster and allow surgeons to have shorter residencies?

My wife is a resident surgeon, and she works obscenely long hours. I don’t believe this is a necessary process to put our healthcare heroes through. So I am interested in trying to streamline surgical education.

What does a typical day in the lab look like for you?

In the HAMR lab, I have been learning a bit about the mechatronic design side of devices used to collect experimental data and updating previous students’ devices. But in general, a typical day for me often involves using MATLAB to analyze data on a human subject experiment that I or someone else has collected previously. Depending on how cleverly the experiment was set up sometimes we can immediately analyze the data and test a hypothesis related to human motor control. Other times, making sense of the data can take months to years. Humans are so variable and so are their data so, you never know what you are going to get.

Any hobbies and interests outside of engineering?

I grew up playing sports a lot, mostly basketball and football. When I got to grad school, I picked up rugby, which was very fun. I’m considering playing here, but I think the body’s beat up. Might be time to call it quits. But Saturdays and Sundays, I’m definitely watching all the football games.

Interview conducted by Jonathan Deutschman