A team led by Johns Hopkins University engineers figured out how and why human cells move much faster through thick mucus than thinner varieties. The findings could inform and inspire new treatment for mucus-related diseases, including chronic lung diseases and mucinous cancer—the deadliest subtype for lung and ovarian cancer.

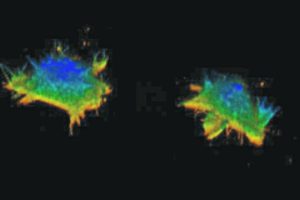

People sick with certain diseases, including asthma and COVID-19, secrete mucus that is 2,000 times thicker than normal. But cells have fin-like “ruffles” that help them sense viscosity and know when to change shape to power through the thickest mucus, the researchers found.

Previously, the ruffles were considered useless appendages, but the engineers discovered that the ruffles propel cells through thick mucus, helping them to swim faster in the thick stuff than more watery fluids.

The findings were published today in Nature Physics.

The research team was led by Yun Chen, assistant professor of mechanical engineering, and included members from the University of Toronto and Vanderbilt University.

This research project is supported by Air Force Office of Scientific Research (AFOSR), National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Science Foudation (NSF), and Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.